Sanctions lists are published by many institutions, including the UN Security Council, the US and UK Treasury, the EU foreign service and many others. Between these lists, there is both overlap and disagreement: for example, 12 separate sources target Han Se Pak, who leads the North Korean arms trading organisation KOMID. On the other hand, Yevgeni Prigozhin, the man behind the famous St. Petersburg troll farm "Internet Research Agency" and the private military group "Wagner", is named on only five lists.

In order to provide an integrated view of such entities, OpenSanctions needs to establish a mechanism for entity integration. In this article, we want to describe our approach to this challenge in terms of its three key steps: blocking, matching and integration.

Before we describe these steps in detail, lets first discuss our goals for de-duplications:

- Uniqueness. At the end of the process, we want each logical entity - person or company - to show up in the combined OpenSanctions data exactly once, presenting the attributes (like identifiers, addresses or descriptions) from various sources.

- Precision. Our appetite for incorrect matches between the lists is extremely limited. For example, we need to be prepared to keep individuals apart even if they have the same name and nationality.

- Transparency and reversibility. The system must keep an audit trail of the matching decisions that have been made. If such a decision is later found to have been incorrect, there must be a way to undo the error and establish a correct set of matches in its place.

With these objectives in mind, let's dive into the first challenge: finding possible duplicates.

Blocking entities into possible matches

The first challenge with integrating the dataset is the number of matching links that could exist: the 130,000 entities in OpenSanctions hold the potential for almost 17 billion pairwise comparisons.

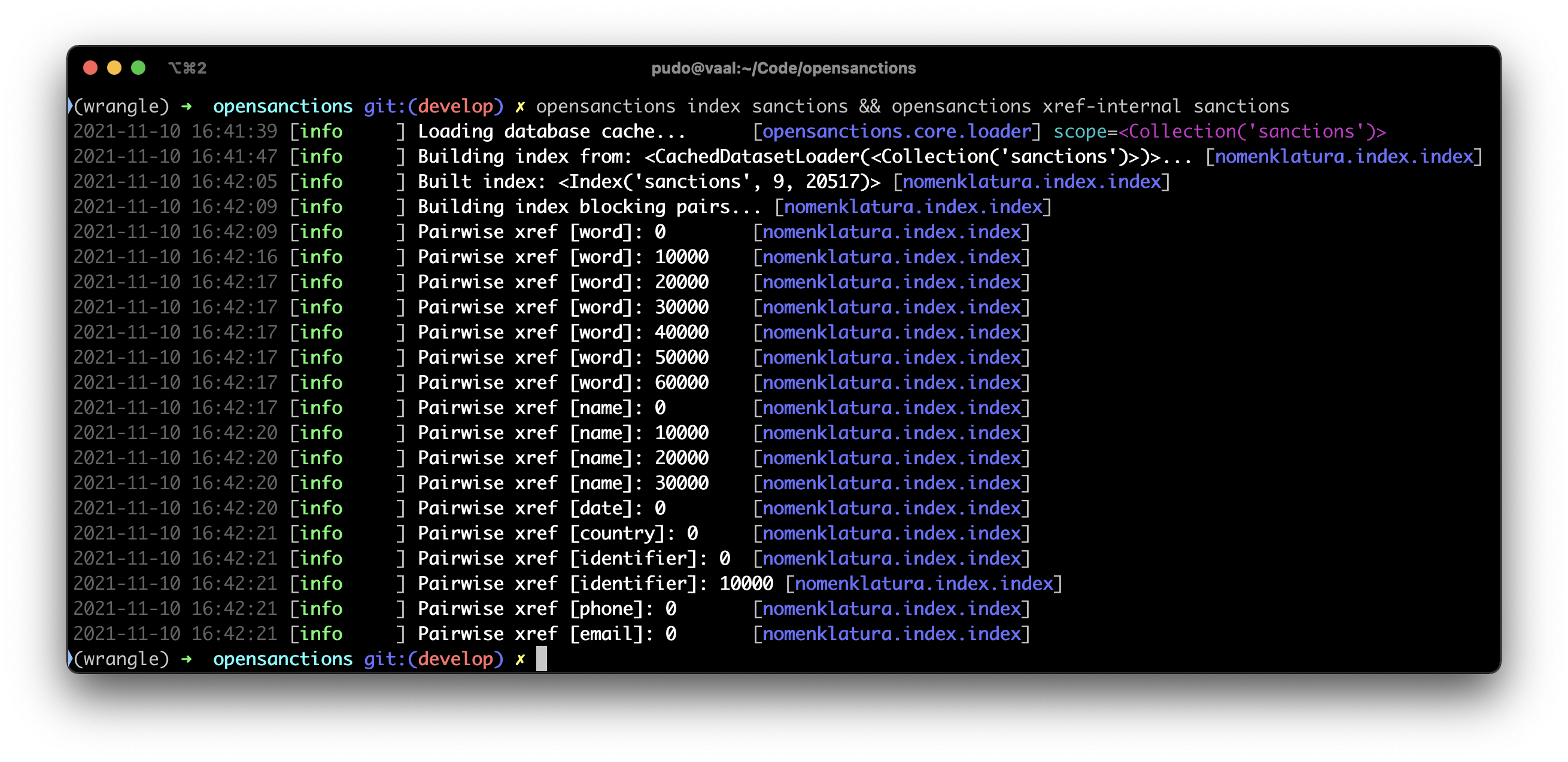

To avoid needing a supercomputer, it's common in entity resolution to use a strategy called blocking: building small buckets (or blocks) of entities that are known to have some shared properties, like phone numbers, name parts, tax numbers or other details. What's interesting about this process: the obvious way to do it is by building an inverted index of the entities - essentially a small search engine.

Tuning OpenSanctions' blocking mechanism has been a challenging task: the system now considers term frequencies in scoring possible candidates, handles text transliteration into the latin alphabet, and it is tolerant against spelling variations thanks to its ability to compare character fragments (so-called ngrams) in names.

At the end of this step, we are left with a ranked set of pairwise matching candidates: Company X on the French sanctions list looks a whole lot like Company Y on the UK list - someone should check that out.

Matching entity pairs

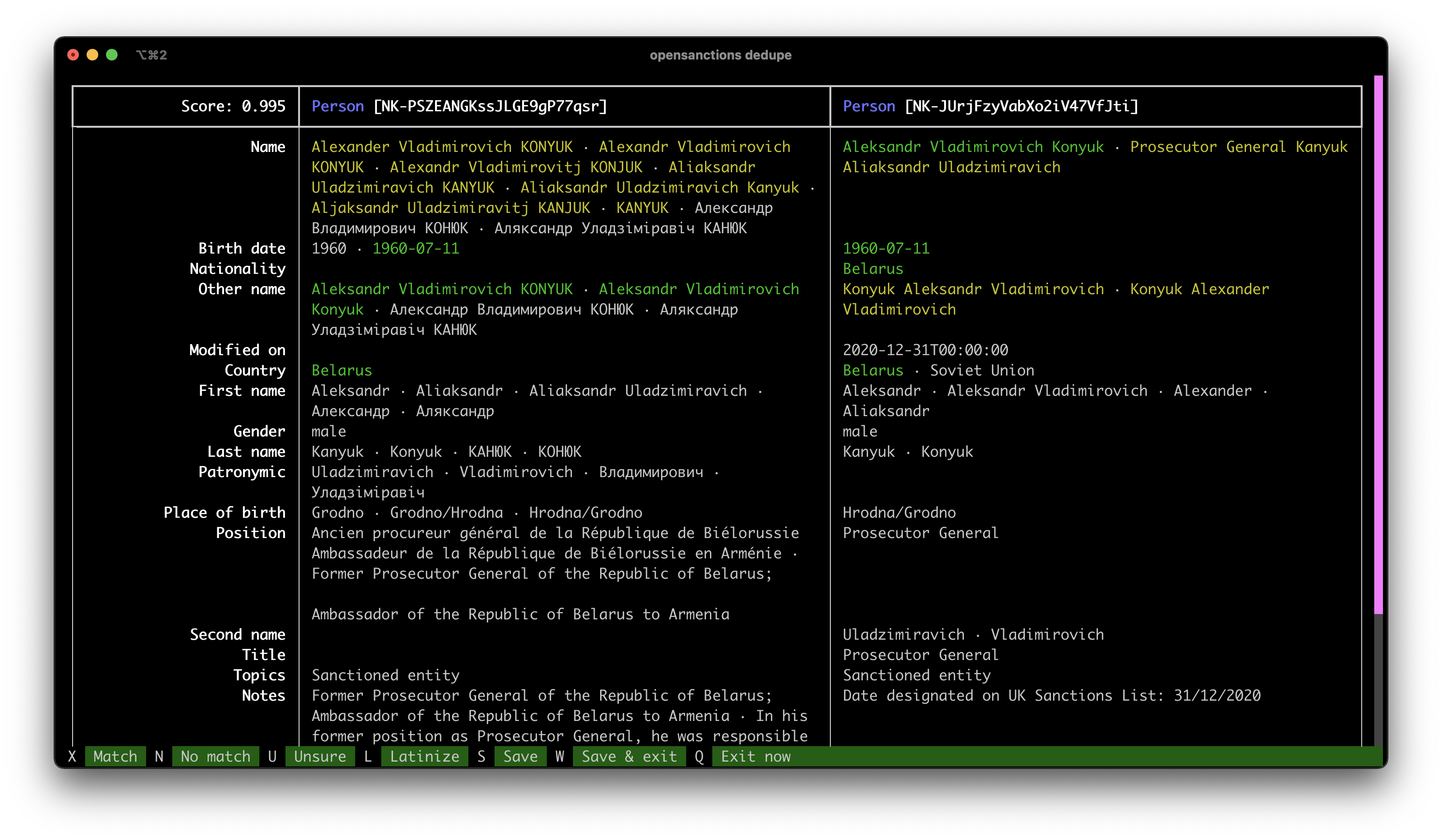

With thousands of scored pairs in hand, its time to make some decisions: do two given records refer to the same logical entity? Given OpenSanctions requirement for a high level of precision, we chose a radical approach to this: manual de-duplication.

Using the brilliant textual framework, we developed a text-based user interface that would present the details of two entities side-by-side and allow the user to decide if both are a match. While most of the time the presented information is detailed enough for an analyst to make this judgement, in some cases we opted to conduct further research on the web to verify that, for example, certain members of the government of Venezuela are subject to US sanctions.

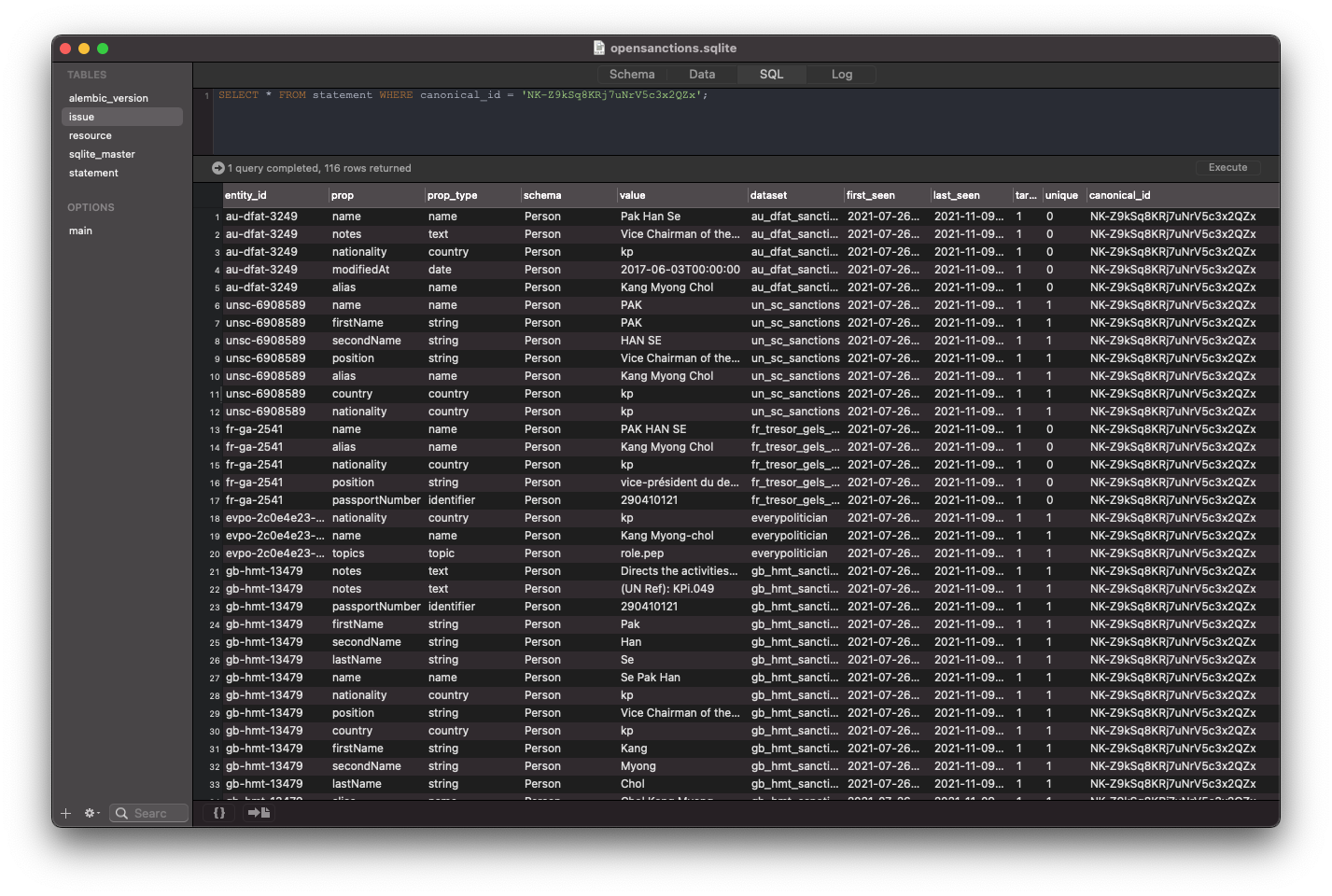

One important decision we made in this system is how we store matches: when a user decides that, for example, the records unsc-6908589 and ofac-20601 refer to the same logical entity, that decision is used to mint a new, canonical, ID - NK-Z9kSq8KRj7uNrV5c3x2QZx - which is going to be used to refer to the combined entity going forward. Further positive or negative decisions are then attached to the same canonical ID. This design makes it very simple to reflect and manage the merged entities without assigning priorities or preferences to specific sources.

(In the future, we plan to mint a third class of entity ID that reference Wikidata, the structured data version of Wikipedia, and which assigns its own identifiers to notable people and organizations.)

Over the course of the last 8 weeks, we have used this tool to make 34,600 manual matching decisions. From the 31,000 positive outcomes contained in this, we're also able to infer another 300,000 negative pairs by assuming that certain sources (e.g. the US sanctions list) have no internal duplicates.

This corpus of decisions should provide a valuable resource going forward, especially for experiments in adopting different types of machine learning to partially automate the deduplication for cases in which sufficient information for an automated decision is given.

Building an integrated dataset

Resulting from entity resolution is a graph of entity IDs, reflecting the positive and negative judgements that have been made (it's actually a very simple SQL table). Computing the connected components on that graph gives us a set of all entity groups to be merged.

Next, we need to apply these merges to the data itself and combine the source entities into a new, combined form. This is where the unusual data model used by OpenSanctions comes into play: the system stores all entities as a set of statements. Each statement describes one value for a property of the entity. For example: the entity ofac-20601 has the property name with value PAK, Han Se according to the dataset us_trade_csl on 2021-10-03.

In order to export data into formats like CSV or JSON, these statements get read from the database and assembled into entities. This creates the necessary flexibility to export combined entities without modifying or destroying any of the original data - keeping the option to reverse a merge decision at a moment's notice.

The ability to mix and match statements from multiple sources allows OpenSanctions to export different versions of each entity. For example, a sanctions target from the US list will be exported as part of that dataset with only the properties published by the US government. However, the entity would be merged up with properties from all other sanctions data in the version published as part of the Consolidated Sanctioned Entities collection, and it might even be further enhanced with facts from Wikidata in the even broader Due Diligence collection.

A re-usable toolkit: nomenklatura

Much of the functionality needed to deduplicate OpenSanctions sources fits as a natural extension on top of FollowTheMoney (FtM), the data ontology used by the project. Indexing and blocking entities, the interactive de-duplication user interface, and the code for resolving entity IDs after they have been merged are all independent from OpenSanctions core business.

That's why we're releasing the entity resolution technology described here as a re-usable open source toolkit, nomenklatura. Nomenklatura is installable from Python's package index and depends only on FtM. It can be used as a command-line tool or Python library and provides easy deduplication and data integration functionality for any FollowTheMoney dataset. Check out the README for a walk-through of the tool.

What's next?

Our approach to entity deduplication and resolution is fully deployed and has proven a stable technical foundation for the project. While the OpenSanctions data isn't yet fully de-duplicated, this is work in progress.

Even more exciting is that the ground truth data we have generated through this effort can be used to develop more sophisticated matching techniques in the future (in parallel to a similar effort at OCCRP). This may include rule-based entity matching approaches, a regression model to weigh decision criteria, or even methods to convert entity representations into a vector model.

The technology used to match entities across data sources can also be applied to another, broader challenge: matching OpenSanctions data against other foreign datasets as part of a know-your-customer (KYC) entity matching API. Stay tuned!